Many of my earliest memories are of sitting on the blue and white tiled countertops in the kitchen of my grandfather’s beach house watching the cook, Maria Louisa make tortillas. The house was deep in the jungle on the Pacific Coast of Mexico near Chamela – a small fishing village 100 miles south of Puerto Vallarta in the state of Jalisco.

We ate breakfasts at the large equipale table beneath the palapa – a traditional large woven canopy – beside the pool on the cliffs above the ocean. Breakfasts consisted of fresh fruit – sliced mangoes, melon and papaya – then soft-boiled eggs mixed in cups with salt, pepper and chunks of bread that absorbed the rich yellow yolks. There were always fresh bolillos with orange marmalade and we would eat in the cool morning breeze listening to the waves of the Pacific Ocean crashing against the rocks beneath us.

For dinners we sat inside at the long dining table and ate dishes like Huachinango a la Veracruzana (Veracruz style Red Snapper), which was served whole in a tomato based sauce with olives and capers. For years my favorite dessert was Maria Louisa’s flan with the extra caramel sauce poured over the custard.

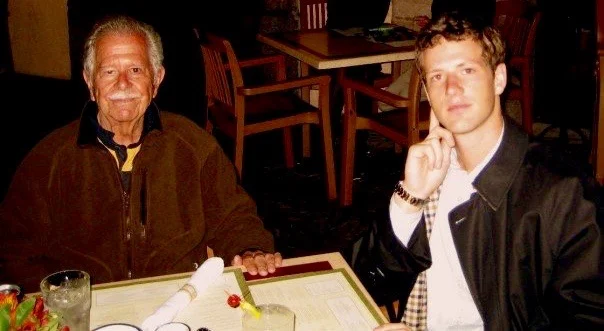

After dinner I would sit with my grandfather in the great room and play gin rummy beneath the lamp on one of the side tables or outside watching the bats feasting on the veritable buffet of insects inhabiting that stretch of the semi-arid jungle. My grandfather always said that if it weren’t for the bats, the insects would be so thick we could never have had the house there. In the morning I would wake to the early light coming through the wooden blinds over the screened window and the sound of the young man sweeping the guano from the terraces around the bedrooms of the house.

My Grandfather loved good food.

To my knowledge, the man never cooked for himself. Living in Mexico, he always had a full-time cook on staff and he took an active role in both their culinary development and the creation of his day to day menu. Some of the greatest cooks I have known were those employed by my grandfather.

He took great relish in organizing his food; later in life when I visited his condo in Mexico City or his home in Morelia – a small colonial city in the mountains three hours north-west of the City of Mexico – we would always have terrific meals that had been planned for months in advance.

Dining with my grandfather in Mexico required an open mind. There were never options on the menu. He wanted everyone to experience all nature of traditional cuisine from fried grasshoppers swallowed whole (he enjoyed relating how the hairs on their legs cleaned out his esophagus), or enchiladas de huitlacoche (a black fungus removed from ears of corn), to my favorite barbacoa (marinated and slow cooked goat meat in a pit lined with cactus leaves), or one outstanding Carne a la Tampiqueña at an historic restaurant several blocks away from the Zocalo in Mexico City.

When dining with my grandfather one could not be squeamish.

When traveling he was serious about trying the local cuisine and was open and generous in ensuring we enjoyed the finest examples.

In Moscow we had borscht with a spoonful of rich sour creme and I had an excellent Rabbit Stroganoff at the CDL (The Central House of Writers) Restaurant. In St Petersburg we ate braised bear with wild forest mushrooms.

In London we had a roasted Prime Rib at the Georgian Restaurant on the top floor of Harrods – a massive cut designed for two people, wheeled out on a trolley with a number of accoutrements including roasted vegetables and potatoes. We had Steak and Kidney Pies at Rules – the oldest operating restaurant in London. We also had wonderful pork sausages with mashed potatoes and gravy on the small second floor of the Lamb and the Flag Pub in a little square in Covent Garden and Bone Marrow with grilled vegetables in a restaurant in the British Museum.

Dining with my Grandfather was always an experience. Regardless of the location, every meal was an extended formal affair. While he rather enjoyed the atmosphere of old British pubs, he detested ordering at the bar and preferred to place his order with his dining companion (yours truly) and have them relay it to the proper authority.

My grandfather was also a harsh critique. To him it was a cardinal sin to over-boil an egg; a fact I learned along with several Hungarian waitresses and at least one breakfast cook when, on our fourth morning in London (and his fourth disappointing breakfast) my grandfather decided that negotiations had failed and direct action was called for as opposed to further delegation. He took his cane from the adjacent chair and marched into the kitchen. I however, found my eggs perfectly over-easy and doubting highly they would be improved by my joining the crusade, remained table-side eating contentedly. Several minutes later he carried the bowl out himself accompanied by several flustered Hungarians and sat down to enjoy his meal.

The following morning when his eggs arrived barely over raw he merely cocked his head, said “well”, and ate them resignedly.

For a man who in all probability may have never cooked in his life, he knew a remarkably extensive amount about food preparation. One of my last memories of him took place while he and I were having lunch during our voyage on Russia’s Volga River. We were dining with several other travelers and he described for our companions the process of preparing the cold walnut cream sauce with pomegranates his cook used on traditional Mexican stuffed peppers.

Preparing the walnuts was a complicated process, both difficult and time-consuming and impressive to hear described by a man whom I had only witnessed enter a kitchen in order to place an order with his home cook, to prepare his nightly cocktail or as a hungry 85 year-old, intent on enjoying a properly boiled egg.

Among other things, my grandfather loved good food and I was fortunate to learn much from him. My meals with him were experiences I will certainly never forget.